I just spent the better part of the morning absorbing the crazy accomplished Anne-Marie Slaughter's amazing article for The Atlantic called "Why Women Still Can't Have It All". Go! Go read it now!

One of her main points that she makes early on is something that really resonates with me (despite not even being a mother yet):

I’d been the one telling young women at my lectures that you can have it all and do it all, regardless of what field you are in. Which means I’d been part, albeit unwittingly, of making millions of women feel that they are to blame if they cannot manage to rise up the ladder as fast as men and also have a family and an active home life.

So instead of blaming women and their supposed lack of personal ambition, we all need to look at the societal structures in place that make it impossible to successfully balance work and home life-- from the obviously bad stuff like crazy long hours and no family leave, to the most subtle but equally detrimental stuff like having an office culture where women feel guilty about not being able to go in on Saturday because you have to and WANT TO go to parent teacher conference.

What I found perhaps most refreshing about the article is that she has some concrete suggestions. Very often I feel like I read an article like this and early on I'm going "Yeah! You're right! Women have come so far and yet here we are still struggling with this basic need," to "Well, it looks like we're just fucked."

Most of her suggestions come down to a need for flexibility--in hours, in where you work--which she acknowledges cannot be the reality for every career. And I completely agree with her assistant who wrote her and said, “You know what would help the vast majority of women with work/family balance? MAKE SCHOOL SCHEDULES MATCH WORK SCHEDULES.” I've been saying this for years too! Ever since I was in elementary school and hanging out in the After School care! Why are we still tied to an educational timeline of 8-3/September-June that allows for a fucking farming society?

The part of her article where I got most excited-- the part that felt the most new and risky to me-- was when she went out on a limb and said that while having a supportive life partner who will make sacrifices with you is important,

...the proposition that women can have high-powered careers as long as their husbands or partners are willing to share the parenting load equally (or disproportionately) assumes that most women will feel as comfortable as men do about being away from their children, as long as their partner is home with them. In my experience, that is simply not the case.

Here I step onto treacherous ground, mined with stereotypes. [Do you ever!] From years of conversations and observations, however, I’ve come to believe that men and women respond quite differently when problems at home force them to recognize that their absence is hurting a child, or at least that their presence would likely help. I do not believe fathers love their children any less than mothers do, but men do seem more likely to choose their job at a cost to their family, while women seem more likely to choose their family at a cost to their job.

Meowza! I love that she goes for it. MEN AND WOMEN ARE DIFFERENT. Why is that so hard to say? Why do I even feel guilty writing that? Maybe because for years, feminism has seemed to mean that women can be and have what men are and have. This implies that the male experience is the normal experience, the one to strive for. I totally felt that growing up in the 90s, and throughout all of my schooling experience I felt like it was true: I could literally do everything the boys could do, and sometimes even better.

And then things changed.

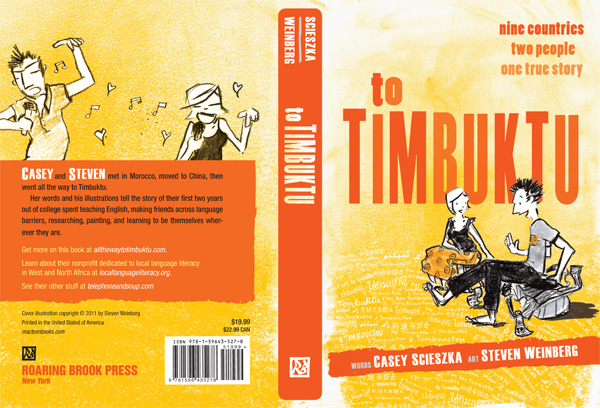

Weirdly, a big part of when that all came crashing down for me was learning how to rock climb with my 6'2" boyfriend at 24. I'd been an athlete for years, a captain of loads of teams, but I stopped playing sports in college when the time commitments for teams became ridiculous and interfered with my classes. So Steven never knew me as an athlete. I was determined to show him that I was.

(My high school bball team. I'm on the coach's left with a mop of badly dyed hair.)

We climbed a lot because we lived and worked right by a rock gym and as the months wore on I got better and better but only to a certain point.

(By the way, yes I am fake climbing in the 1st photo but actually climbing in the 2nd.)

There were climbs that I would physically never be able to do because I am 5'4", my hands are proportionately small, and I've got the muscle build of a 20-something woman. Sometimes my boobs would literally get in the way of holds. And OH MY GOD DID THAT PISS ME OFF. What had been a great form of physical and mental bonding between us eventually became something of a nightmare. I'd been told my whole life I could do anything, and here was my body showing me very clearly that I couldn't and it made me really fucking mad. Often, irrationally at Steven.

It became important to me to have female climbing partners which I found in my dear friends Kate and Lauryn.

But still, it really bothered me that I even wanted that.

Of course I always intellectually understood that my body would not be capable of certain things, but what was most upsetting was that climbing triggered this whole waterfall of emotions and doubts: what else can I not do like Steven because I'm a woman? It made me feel like all of those "You can do it girls!" promises I'd grown up with were empty, short sighted, and setting me up to feel like a failure down the line. Exactly like Slaughter says.

Sadly, it didn't occur to me to ask myself a much more productive question like, "What can I do because I'm a woman?"

By the way, I'm sure the fact that at that time I was babysitting a lot only compounded my feelings that pregnancy and children and all other womanly things would be the end of me and that I would have to be very vigilant about how and when kids appeared in my life if I was ever going to amount to something. AND EVEN THEN, like Slaughter is now asking, could I really have it all? Probably not. Definitely not in the sense that we've all meant it for years.

But to go back one paragraph, I want to end this by promising to to myself that I will no longer back away from my femininity as a way to supposedly achieve equality with men. I will allow myself to ask "What can I do because I'm a woman?" and more importantly, I will allow myself to answer.